I get the text while sitting defeated in my car on the side of the road. I’ve been searching for a place called Gun Powder Falls, and I’m staring at Google Maps when my phone pings with a message from a friend.

Sinead left us.

It takes a moment to sink in, to fully comprehend.

Sinead O’Connor, who struggled with mental health issues her entire life, who had the same diagnoses — bipolar and borderline personality disorder — as the sister I lost to suicide just seven months prior — is dead.

I go to Spotify, find a playlist, and put on Troy. My hands are trembling. Immediately I am transported to nineteen-ninety. To my twenty-one-year-old self who does not (yet) know how to name trauma or ride the edge of ache. Who turns to boys and booze and posturing. Who is irreverent and scared and always the first to leave. Leave a guy alone in my bed the following morning. Leave a job that makes me antsy. Leave a town so empty and permeated with strife that intuitively, I know if I don’t leave now, I never will. A pile of plastic cassette tapes heaped on the car floor; I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, scribbled in ballpoint pen on a label. I am a girl, perhaps not so different from Sinead.

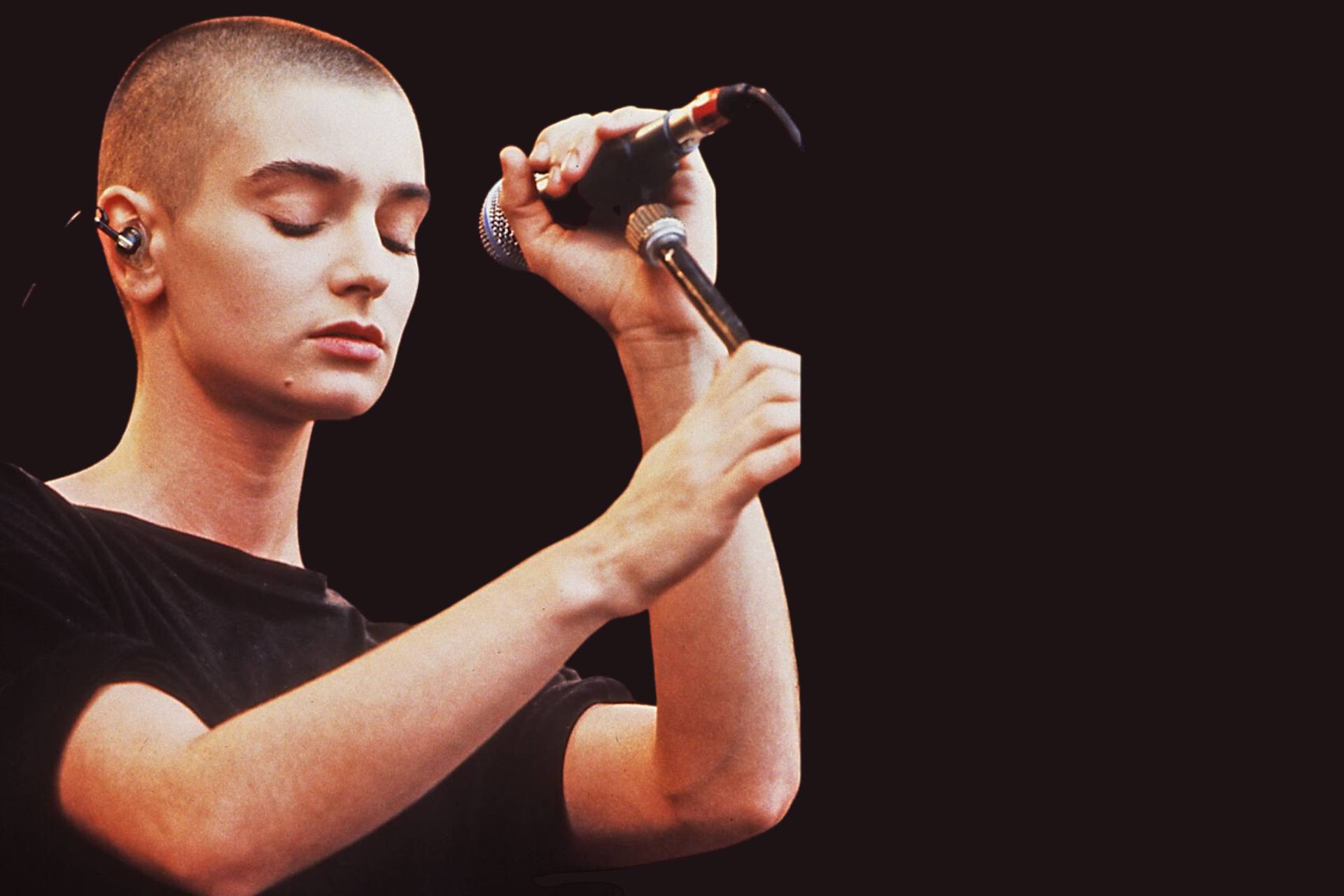

I was a massive fan of O’Connor in the early nineties; was as smitten as any boy with her wide green eyes, shaved head, low-hung boyfriend jeans framing the white edge of her hipbone, her wiry tattooed frame. When she sang, Nothing Compares to You, her eyes boring straight from MTV through the thick lead glass of our Zenith Console screen and deep into my adolescent soul, I swooned. I wanted to be her and be with her. To howl and keen and emanate music at once ethereal and primal. To piss everybody off and still garner love and adoration and accolades. Something Sinead seemed uniquely capable of — at least for a while.

But it never lasts.

In time, women like Sinead always fall from grace. Eventually, she ceased being MTVs darling after a series of jaw-dropping incidents: the boycotting of the Grammy’s; the tearing up of a photo of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live. Her willingness to criticize the system and stand behind her beliefs could seem reckless, but it was also brazen, an uncontainable ferocity emanating love, truth, and care. A voice for a generation rebelling against the felt hopelessness of a post-industrial future, a black X struck across our chests, a Cold War simmering in our psyches. She was a feral flame staring down the wind, so her combustion seemed inevitable.

It’s too soon to know how Sinead O’Connor died. Part of me hopes we never will. A suicide or accidental overdose is always layered with culpability, providing fodder for the masses and a mirror if we let it. Sinead was always a reflection — a placeholder for our projections. So we cheered and heckled and shunned. I have no desire to see her death go down that way.

What if we had to reckon with more than the tragic loss of an eighties pop-rock icon? What if we had to sit with the notion that Sinead O’Connor did not leave us but that we left her? What if we took in that twenty-four-year-old hollowed-eyed girl staring back at us from the SNL stage — the girl who made our parents squirm, pissed off Frank Sinatra, and was exiled from the music industry — the girl who was a poster child for childhood abuse, mental illness, and addiction?

What if we said these words, uttered them out loud, and shot them straight through heaven: We left Sinead O’Connor long before she left us — like we leave so many, and so, it is understandable that she reached her moment of enough.

Godspeed, Sinead. You will rise.