Interview with Ian Kerner

When a couple first comes to sex therapist Ian Kerner for a session, he always asks them to tell him about the last time they had sex.

“Most couples wait far too long to come to sex therapy and are in pain,” Kerner says. “They’ve been self-silencing and simmering and are feeling pretty hopeless. In that first session, I want to get them out of pain, so I’m very solutions-oriented.”

Asking anyone to describe the last time they had sex reveals a lot, about his experience: It’s a detail-rich story that has a beginning, a middle, and an end. It reveals what worked and what didn’t. How did they decide to have sex? Who initiated? When and where did the event occur? How did they generate sexual excitement? How did they amplify and intensify the arousal? What behaviors did they engage in? What behaviors didn’t they engage in? What was off-limits and why? Who had orgasms? Who didn’t? What was the emotional and psychological impact of the experience? Did the sex leave them motivated to have more? If not, at what point did things stall?

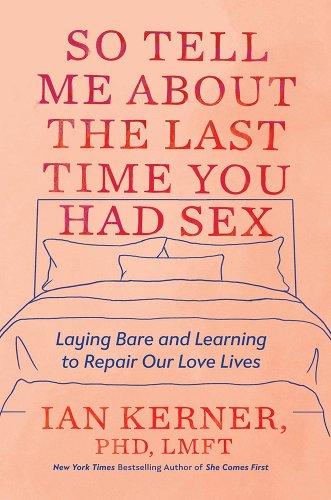

Kerner’s point is: That single prompt brings forth a lot of significant information to reflect on. His latest book, So Tell Me about the Last Time You Had Sex, helps translate some of those questions into insights that don’t necessitate going to see him for a session. A big part of the process—and the homework—is learning to understand your sex script, a concept he explains in this interview.

What’s a sex script, and how can it be useful?

A sex script is the sequence of interactions (physical, emotional, psychological) that underlie the last time a couple had sex. Most couples I work with have a kind of default sex script, and if they’re coming to see me, then most likely their sex script is reinforcing the problem rather than helping.

My job is to help couples understand and rewrite their sex scripts. To a fly on the wall, the sex script is the progression of actions: clothes coming off, mouths finding each other, hands exploring, body parts joining and unjoining, muscles tensing and releasing. But beneath the surface of the sex script is an emotional underground: the mental space between bodies. Sometimes sex is a bridge; other times it reveals a chasm. When the sex script works, we lose ourselves in arousal. Sex becomes like a familiar dance, and we don’t think twice about the choreography. But when the sex script fails, it’s all we can do not to ruminate over the details.

I know that, to some, thinking about sex as a scripted event, with various elements that unfold in a sequence, may sound rigid, overly clinical, and off-putting, the opposite of spontaneity—which is what sex is “supposed” to be, right: spontaneous. But I liken my overall approach to playing jazz. Sure, you want to improvise and cut loose, but in order to do that, you and your partner need to know what song you’re playing, the genre, the key and chord progressions, the tempo, and so on. The legendary jazz bassist Ron Carter said of playing in the iconic Miles Davis Quintet from 1963 to 1968: “We were looking at every night going to a laboratory, Miles was the head chemist. Our job was to mix these components, these changes, this tempo, into something that explodes safely every night with a bit of danger.” That sounds like good sex to me—exploding safely with a bit of danger—and to do that, you have to know all the components you’re mixing.

What are the key elements of a sex script?

There are a few key elements: first, having a shared desire framework. Sexual desire discrepancies are the number one problem I deal with. And it’s usually not because either partner is lacking in desire but rather because they’re in different desire frameworks. My job is to help them create a sex script that has a shared desire framework. Also, with heterosexual couples, the sex script is usually dominated by intercourse, and most couples get there within just a few minutes of starting. That doesn’t leave time for much else. And we know that most women do not experience orgasm from intercourse alone, so many women are getting left behind.

But let me ask you, how many gay men do you think engaged in intercourse the last time they had sex? The same? Higher? Lower? According to a study of 25,000 gay and bisexual men about their most recent sexual event, only 35 percent had intercourse, which certainly challenges the idea that gay sex equals anal sex. So if they weren’t having intercourse, what they were doing? Engaging in twelve different common behaviors that won’t come as a surprise: things like kissing, hugging, manual and oral stimulation of the genitals. But what might be surprising is that gay men put these behaviors together in 1,300 different combinations! Thirteen hundred different sex scripts, 65 percent of which were not based on intercourse but rather on outercourse behaviors.

I want couples to have a shared desire framework and add more outercourse behaviors to build arousal. But I also want their sex scripts to be more than just a sequence of behaviors. Sex scripts have to be sheathed in eroticism. There needs to be mind-based arousal, not just physical arousal. Some women can fantasize their way to orgasm. Men often get hands-free erections. We need to bring this erotic energy and mind-based arousal into partnered sex. And as much as a sex script is about turning on, there is also a point where we need to go into a mutual flow state and allow our brains to turn off. Our bodies need to go into a state of sexual autopilot so that we’re not thinking about sex—we’re simply present and in the moment. And then enjoying the bliss of orgasm and the warmth of connection that follows.

And we need an erotic thread between sexual events. We need to live in a way that our erotic selves can make an appearance and connect. Not to have sex but just to keep eros in the air.

What are the different desire frameworks, and what do you do if you and your partner aren’t on the same page?

Some people (often men) have high sexual metabolisms. They can gobble up a single sexual cue—like seeing their partner come out of the shower—and it goes straight to the genitals. They’re ready, willing, and able. This is what I call highly reactive desire. It’s like being at an amusement park and having a fast-pass to get on a ride. You just walk right up, you get on, and you’re off. But very often, a person with highly reactive desire might be paired with someone who doesn’t metabolize a sexual cue as quickly. They need more than one cue; they need a steady stream of cues to simmer and percolate. This is what I call deliberative desire. In this case, the partner with the fast-pass has to be willing to slow down and wait on line and help move things along. They need to get in sync and focus on early-stage arousal.

What’s your advice for cultivating early-stage arousal? And then sustaining it?

For most couples, foreplay is usually a little bit of kissing and then straight to genital stimulation. They’re missing all of the above-the-waist and above-the-neck arousal. It’s important to take the time to get sensually warmed up—to have an arousal runway—and to include mind-based psychological arousal. By this I mean our ability to share fantasies, play with them, talk about the sex we’re having, and tap into our core erotic themes—specific fantasies that turn us on.

We all have erotic themes that resonate more than others, even if we’re not sure what they are. I help couples get in touch with their erotic selves and then get those erotic selves talking to each other. But most couples aren’t ready for that kind of face-to-face psychological arousal—they need some help. So I start by asking them to begin with side-by-side arousal: taking in some literary erotica, or erotic podcasts, or audio or ethical porn, in which the performers really want to be there. The point is to get mind-based arousal into the sex script one way or another.

How do you give helpful feedback to your partner about what’s working and what’s not?

Couples come into my office overspilling with anger, impatience, frustration, and a sense of defeat and hopelessness. How do I help them start the process of expanding their sex scripts, sharing their vulnerable erotic selves with each other, and nurturing an erotic flow state? How do we move from hopeless to hopeful, which is the goal of the session?

I always ask a couple a question that is future-oriented: “If we were to work together for just a few months, meeting every other week or so, with homework in between, and things were to improve in a concrete way—if sex were to get better—what would better look like?” I want them to stop complaining about a problem and to start envisioning a solution and to do so in a form that resembles a fantasy. The poet T.S. Eliot used the term “objective correlative” to describe how good art (in his case, poetry) evokes emotion in the audience or reader. In asking a patient or a couple to visualize a sex script in positive erotic terms, I’m encouraging them to create an objective correlative of a new sex script, something they can quickly conjure and refer to that often evokes arousal. And if the session is going well, if both partners are willing, the heat in the room starts to rise. Because that’s the power of sexual language and the erotic correlative: to summon and manifest arousal.

The point is: Don’t just talk about a problem as a problem; talk about the solution. Then turn the solution into fantasy and share that. If you’re too shy to share the fantasy, then tell your partner you had a sexy dream about them and blame it on your subconscious. When they ask you to share (and they’d better), fill in the blanks with your fantasy of better sex.

Talking about a relationship problem is often challenging, but it’s especially challenging when it feels like you’re the problem that’s being talked about. How do you remain vulnerable and empathetic when you feel attacked and your instinct is to defend yourself? In these situations, I often try to work with couples to externalize the problem and see it as something that can be walked around and looked at and reflected upon as its own separate entity. When externalizing in this manner, neither partner is the problem; the problem is the problem, and as such, it can be decoupled from any one partner’s personal identity. An issue of erectile unpredictability during partnered sex, for example, is just that—a problem that occurs during partnered sex—and not the fault of a partner who is “impotent.” Talking about a problem with early ejaculation is different from identifying a person as a premature ejaculator. Talking about low desire in a relationship is different from identifying a person as having no desire or being frigid or sexually shut down. I find when I encourage patients to externalize a problem and put it out in front of them, they are then able to approach the problem with genuine curiosity, candor, calm, and a sense of collaboration.

What’s the homework assignment you would give to a couple wanting to start the work of rewriting their sex script?

Generally, I’ll listen to a couple describe the last time they had sex, and I’ll target the earliest point in the sex script that needs work. Usually, it’s something like adding psychological arousal or engaging in more outercourse behaviors or just showing up to be sexual. I call these assignments willingness windows because I’m not expecting couples to show up for homework with strong levels of desire, but they can have the willingness to show up because they know it’s important.

With sex, as with many things in life, having the willingness to engage is the most important part of the process. I can work with couples who have all sorts of issues and impasses: anger, lack of attraction, sexual-function issues, like erectile unpredictability. It can seem daunting, but if both partners have even incremental amounts of willingness, then the situation is workable. These willingness windows are not about having sex; they’re about engaging in a specific activity that is decoupled from sex and focused on one aspect of the sex script.

How can this work be helpful for people who are not in serious relationships?

Most of us didn’t grow up in sex-positive homes. We grew up in sex-negative homes where sex was a source of shame, or we grew up in sex-avoidant homes where sex was rarely if ever, discussed. The result is that sex wasn’t mirrored to us in a healthy way and we didn’t grow up with a vocabulary to talk about sex in the way we learn to talk about all sorts of other topics.

The sooner you start to think about what you need in a sex script, the sooner you have both a structure and a language to communicate your needs. If you’re single or not in a serious relationship, sooner or later, it’s likely you will be. Don’t be one of those people who have waited too long to discuss a sex problem and come to see me when it’s often too late. In knowing your sex script—and how you want sex to occur in action—you’ll learn a lot about your authentic sexual personality and how you want to express it.

This interview, which originally appeared in Goop, was republished on NCCT’s Loving Well with permission from the author.

About the author:

Ian Kerner is a licensed psychotherapist and nationally recognized sexuality counselor who specializes in sex therapy, couples therapy, and working with individuals on a range of relational issues. He is the New York Times–bestselling author of She Comes First. His newest book is So Tell Me About the Last Time You Had Sex. He is a clinical fellow of the American Association of Marriage and Family Therapists, and he is certified by the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists (where he also sits on the board); the Society for Sex Therapy and Research; and the Institute for Contemporary Psychotherapy. Learn more about Ian’s upcoming training, The Sexually Wel-Informed Clinician (for psychotherapists) happening in Northampton, MA on October 28th, 2022.